A Prologue to the Epilogue

The article is about the peculiarity of the “Women for Peace” campaign initiated by the RA Prime Minister’s wife, Anna Hakobyan, and the reopened talks on peace in the public domain, combined with the stories of peace-building efforts of female figures of different periods of the Armenian reality. The work on the article started parallel to the launch of the campaign. Selection of the topic, the guidelines of the study, and the co-authored editorial work of the text wording was carried out by Anna Zhamakochyan, alongside the author Mariam Khalatyan. The work was almost ready when the campaign, which was aimed at supporting the overcoming of the Karabakh conflict, faced the calamity from which it had originated, the actual warfare. The renewed war delayed the publication of the article rendering its publishing anachronistic in that context. However, both the transformation of Anna Hakobyan’s activities during the war, the freezing of the campaign after the war, as well as the ongoing debates on the role of women in establishing peace became the basis for retrospectively reflecting on the campaign and publishing it revised. In this phase, the editing of the article was carried out by Arpy Manusyan. Thus, we present the article with revised editions (indicating which vulnerabilities of the campaign did not allow to preserve its pacifist core) and added sections (including considerations about transformations of the campaign in the war and post-war periods).

Being Heard

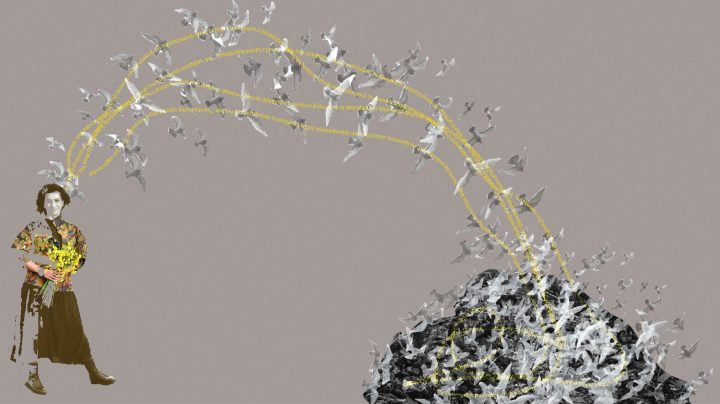

“At that time they did not hear us, the war continued, and the number of victims, prisoners of war, and hostages increased”[1] – these are the words of Arzu Abdullayeva describing the situation in the 1990s, during the Nagorno Karabakh conflict when she and her colleague from Armenia, Anahit Bayandur, began to care about the fates of people captured as a result of the war. At that time, as well as before and after that, the voice of these women (and in general, women who convey a message on peace) was not heard. Regardless, with the help of their supporters and joint efforts, these two women contributed to the release about 500 people from captivity from the Azerbaijani and Armenian sides in the years of the First Karabakh War. This step received attention and an award, not at all local or regional.[2]

From those years up to the present, Arzu Abdullayeva has been the Chair of the Azerbaijani National Committee of the Helsinki Citizens Assembly, and Anahit Bayandur, the co-chair of the homonymous organization in Armenia, was a deputy of the ruling power, the PANM (Pan-Armenian National Movement) faction, in the Supreme Council (Parliament) of the country. The posts held and the efforts made by these women sufficed to make a positive breakthrough in the lives of around 500 people. But only 500.

Arzu Abdullayeva and Anahit Bayandur, like many active women of the time, were convinced that the conflict would not end with the war. Even now, after the Second Karabakh War, it is obvious that the conflict did not end with the war: people want peace (no matter how different the perceptions of peace may be).

Usually (and ordinary) women do not make the decision to wage or not wage a war. They appear in the target of war, that is, in a predetermined “privileged” role, be it a consecrated object, an auxiliary servicing body, or booty seized from the enemy. Women go through the harsh course of wars, bear their consequences, and become targets of attack and defense. Women experience the privations faced by themselves, their children, and the elderly under their care, the multiple burdens of hardships faced by military and civilian men. Women become the parent of the future soldier, the mother of the (fallen) soldier, the wife and supporter of the military man, the victim of sexual abuse, the caring nurse, the support in the back and the housekeeper, the encourager, the comforter, the mother of the future soldier to be born, and sometimes, the hero fighting side by side with the man who, however, will be mostly neglected in the post-war period. Women are responsible for everyone during wars: they stand out for their resilience in crises and the ability to make quick decisions, although these decisions often do not include the wishes of these women themselves (to stay in the war zone or to leave). They are guided by the “orders” of their husbands, and they adapt to the demands of their children, setting aside their own wishes and needs.[3]

According to Cynthia Enloe, “Militaries need women-but they need women to behave as the gender ‘women’. This always requires the exercise of control… This is what is so strikingly revealed in the experiences of women who have been used as the military’s prostitutes, rape victims, wives, widows, social workers, nurses, soldiers, defense workers, and mothers” (Enloe, 2018).

In war situations and in general, as a consequence of the militancy propaganda, the “enemy” on both opposing sides is perceived as “unmanly” – demasculinized, and women are labeled as “mothers of the nation” tasked with producing new generations, giving birth to soldiers and taking care of everyone, of the country while men are at war. In many cases, it is precisely these women who are forgotten after the war.[4]

The Second Karabakh War reinforced the roles assigned to women: thousands of women lost their husbands, sons, and brothers, and appeared in the target of political and public speculation, regularly hearing how to “correctly” mourn a personal tragedy.

Many of these predefined roles were previously largely unavailable to women (e.g, soldier, military nurse) and even a century or a one-and-a-half century ago, aspiring to them in the pursuit of gender equality was considered a progressive step. Some female figures fighting for the advancement of women in public life encouraged their peers to assume statuses that granted a certain active role, albeit militarized, seeing in them the liberation of women from the four walls of a closed domestic, overwhelming, silent life or the confined consumer environment of purely bourgeois life.

At the beginning of the 20th century, one of the Armenian female figures who advocated such a role of women in the war was, for instance, Constantinople-based Armenian public speaker, and educator Mari Beilerian (1877-1915).[5] In the section “The Impact of Women: War and Women” of her work “Depi Ver” (Upward) (1914) she addresses these issues calling on women to recognize and find their special role in times of war (Beilerian, 1914). Throughout her educational, journalistic, and editorial activities, Mari Beilerian tried to create occasions and opportunities for women to be heard in order to increase the participation of women both in the arrangement of family and public life.

In the critique of war, Mari Beilerian attaches importance to the right of people to freedom and self-defense. She strongly condemns war and considers women to be the ones who suffer the most from it. As per her interpretation, the only reason for wars in the world is that the state domineers over people’s rights and fails to establish justice among the population. Beilerian is very clear on this issue: the task of the state is to ensure the welfare of its citizens, and the establishment of justice among them so that people do not exert violence against others and there is no war. Since the state does not do this peacefully, the citizens are left with no other choice but to fight for their rights and justice. Mari Beilerian believes that states seeking power and authority should abandon their ambitions to rule the world and focus on creating conditions for people’s happy and prosperous life.[6] She does not romanticize the idea of peace. It is very clear: peace should be fought for.[7] In times of war, as for Mari Beilerian, women should serve the agenda of the war. She sees the unique role of women in “convincing” men. Beilerian highlights women’s capacity of “irresistible influence” on decision- makers, on men, its motivating power, values “fighting as bravely as men,” “the heroic spirit” with which they fought side by side with men in the past:

“The beautiful young Alanian woman, Satenik, managed to persuade proud Artashes to release her brother from captivity by the influence of her sweet word (…). And the women were aware of that profound and irresistible influence of theirs since they inspirited and encouraged their husbands, brothers, and children during the war. (…) And in South America, on the bounds of the Amazon, there were women who knew how to fight as courageously as men, and who were called Amazons, after an old mythical name. The history of the most ancient centuries and even the present day gives us undeniable proof of the heroic spirit of women. It was not in the remote past when Anita, the wife of the prominent Italian, patriot Garibaldi, lived fighting side by side with her husband, sharing the thousands of dangers hanging over his head. She was the angel of consolation of those dying in the war, she remedied the wounded with the caress of a sister, she reached out to everyone and everywhere, and eventually she herself died of fatigue and privation” (Beilerian, 1914).

Not only Mari Beilerian’s words but also her very life bore the stamp of the war and the internal violence unleashed during and as a consequence of it: she was among the Armenian intellectuals who fell victim to the Genocide. Perhaps, unlike male intellectuals, Mari Beilerian also fell victim to oblivion remaining undiscovered in the established Armenian culture.

Another Armenian female figure, writer Zabel Yesayan (1878-1943), defined the role of women differently in the same period and in relation to the same context (at the same time, being familiar with the French reality through her experience). In 1911, she published a series of articles in the Aragats journal, released in New York, on the woman question, the public role of women, including the role of women in matters of peace. In the article “Woman for Peace,” Zabel Yesayan, addressing particularly the role of women in France, writes that women are pacifists by nature, and she has chosen the path of spreading peace to the generations through the role of an educating wife and mother. Zabel Yesayan writes that women, as mothers and sisters, are against fights and war by their nature, and women are not carried away by the glory of power like men, violence is incompatible with women’s nature and temperament (Yesayan, 1911). Like Mari Beilerian, Zabel Yesayan also believed that if women engage in military operations, it is for self-defense.

Another female figure related to the Armenian context, Lucy Thoumaian (1890-1940), underscored the struggle for peace in women’s activities. She was Swiss by origin and, before emigrating to England during the Armenian massacres with her Armenian husband, Karapet Thoumaian, she lived and worked in the Ottoman Empire. Thoumaian was a part of the international movement founded by female figures who considered the issue of peace as one of the important roles of women since the mid of the 19th century. Lucy Tumayan’s appeal, “A Manifesto to Women of Every Land,” appeared in the official journal of Jus Suffragii (the Right of Suffrage) of the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in 1914 (in the days of the already started First World War). She proposed to organize weekly meetings of women, which should proceed until a secure peace was established: “War is man-made, it must be woman undone” (Liddington, 1989, 91). Lucy Thoumaian suggested that meetings begin with prayer, continue with exhortations to God and governments to discontinue the intolerable evil and sin, and lean on arbitration: “We will do it as mothers of mankind, as sisters of the whole human race” (Liddington, 1989, 91). In 1915, Lucy Thoumaian addressed this call to the Women at the Hague conference representing Armenia there.

“Dear Sisters of Every Land. – Whilst our respective soldiers go bravely to the front, and whilst we at home do what we can for the wounded and the distressed, there is something else still more important to do, of which no one seems to think and which is very specially suited also to the soothing and loving influence of woman. It is the preventing our beloved soldiers to become wounded! It is to work, and this internationally, in the interest of the future peace of Europe.

(Moynagh, Forestell eds. (2012).

More than a century ago, in the days of universal calamity, these women tried to be heard and, importantly, to form a discourse on women’s role and actions, with a secondary role of influencing male decision-makers in winning the war on one hand, and ritual activities promoting the spread of peace through simply bringing women together, on the other. Despite this difference, both approaches are characteristic ideas of the first-wave feminist figures about women, whose role remains within the limits of reforming the male society. This approach will later be criticized, rejected, sometimes supplemented, and sometimes even reproduced by feminists and female figures of another generation.

In modern Armenia also, women think and talk about the (romanticized) role of women in war, the involvement of women in the army or, on the contrary, the rejection of war, the change of the military system, and the fight for peace, especially due to the Karabakh conflict erupted in the 1990s.

Some of them (especially during war escalations) tried to unite, raise their voices, and define their own actions to transform the historical and political questions facing them, their societies, and countries, mainly acting within the framework of self-organized civil initiatives and non-governmental organizations.

It was much rarer, however, that the issue of overcoming the war became an agenda for female figures representing or related to the ruling elite. In the pursuit of this, women advocates for peace were constantly at risk of being marginalized, facing ridicule and hostile attitude, being labeled as traitors, and physically attacked: both in the 1990s, and especially after the political turn that followed the years of war (1998) when the militant ideology began to spread as the dominant truth, and in present, after the Second Karabakh War. While female figures of Azerbaijan and Armenia could still make mutual visits in the days of the intense war in 1992 since the mid-2000s mutual visits have become almost impossible and take place in a third country. This is also suggested by Arzu Abdullayeva’s letter of condolence upon Anahit Bayandur’s passing in 2011, in which she tells about Anahit Bayandur’s visit to Baku in 1992, without already having the opportunity to personally come to Yerevan:

“Our first joint action was paying mutual visits in the days of the intense war: Anahit visited Baku, and I visited Yerevan. I remember how in August 1992, upon arrival in Baku at my invitation, she began her speech in front of an Azerbaijani audience. She said in a calm voice, “I have come to say hello to you.” Then she explained that she had come to prove that our peoples were not enemies, they could not be, and that we had a lot in common. The audience was listening to her. Some listened with respect and admiration, others tried to find flaws in her speech to cling to in order to attack her. But her calm and simple “Hello” left no chance.” [8]

Since the mid-2000s, the dominance of automatically increasing militancy established by the elites of Azerbaijan and Armenia has distanced the two societies from each other and normalized mutual demonization or dehumanization. The semi-war situation lasting decades, the Second Karabakh War of 2020 increased the loss of lives renewing the wounds. The situation that has lasted for years has alienated people in Armenia and Azerbaijan from their vital problem and its resolution, from the acknowledgment of being a part of building peace. After the Second Karabakh War, it became more urgent, however, concurrently more complicated to enable the conversation about overcoming the hostility and the possibility of peace between the parties. Today, talking about the demand for peace requires extraordinary courage which the brave people of Armenia, including women, continue to do.

“Women for Peace”- Before the War

The activities aimed at peace and the involvement of women in it were more or less massively launched with the “Women for Peace” campaign initiated by Anna Hakobyan, the wife of the Prime Minister who formed the government after the 2018 Velvet Revolution.

The turn that took place in the domestic political life of Armenia in 2018 presented opportunities to renounce not only the corrupt elite but also the ideologies fueled by it. In this sense, the declaration of the Prime Minister’s wife about initiating the “Women for Peace” campaign in that political context of Armenia was a groundbreaking and brave step. Not only was this an initiative to shift the discursive course of the settlement of the Karabakh conflict and to direct it towards the establishment of peace, but also to pronouncedly introduce women’s perspective. And what was very peculiar is that this discourse was led from a near-official platform. The campaign was interesting in two respects: firstly, in terms of direct contact with public officials in post-revolutionary Armenia, and secondly, in terms of questioning the established formulations and practices related to women and war issues by a woman.

This did not at all mean that the militarization processes slowed down in Armenia, or that the discourse of militancy was no longer in place, but it should be highlighted that a new stream of pro-peace discourse was formed at the state level, by the Prime Minister, the Foreign Minister, and some members of the National Assembly. It was from this perspective that the promotion of the peacebuilding discourse by the Prime Minister’s wife was significant. In addition, the revolution also enabled the increasing and highlighting of the role of women which created the opportunity and conditions for the implementation of this campaign.

The campaign was launched during a meeting held in Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery in July 2018. Anna Hakobyan introduced the participants to the “Women for Peace” campaign initiated by her, the aim of which was to prevent new casualties in Armenia and Azerbaijan through women’s calls for peace.[9] The message of the “Women for Peace” campaign became known not only within the country but also became a subject of discussion on various international platforms, during conferences, and meetings of the Prime Minister’s wife with politicians (ambassadors, representatives of various organizations, congressmen).

Initially, the activity was mostly outside Armenia: in the USA, Kazakhstan, Germany, and China among others. There was also a meeting in Karabakh, on the frontline, with the participation of various Armenian and Russian female figures.[10] Thus, by using international platforms, the movement gained the opportunity to make the intention and readiness for a peaceful settlement of the conflict widely known and accessible. Anna Hakobyan always noted in her speech that she called on all mothers, and it was her desire that this appeal became global, and was heard on international platforms.

“With all this in mind, I have initiated the “Women for Peace” campaign which aims to unite women from all parties of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict to reject war and join their efforts to save human lives from all parties of the conflict. Our ultimate goal is to create a global network of women for the establishment of peace in Nagorno-Karabakh, as well as in other hotspots around the world.”[11]

With the internationalization of the campaign, on the one hand, the role of the local context of the Karabakh conflict was decreasing, but on the other hand, with the statements about becoming international, the idea of peace and the imperative to settle the Karabakh conflict peacefully were placed in a global context.

There have been successful instances of international campaign initiatives on a regional conflict, such as the “African First Ladies Peace Mission” campaign founded back in 1995,[12] and women’s peacebuilding activities in Liberia since 2002.[13] Therefore, no matter how unique the initiative of this campaign was in our reality, it could claim important results.

The internationalization of the campaign, however, was not accompanied by regional expansion: the engagement of the most important party, the Azerbaijani women, did not take place. The sensitivity of the topic should be taken into account in the conditions of the parallelly unfolding militarization policy which complicated the dialogue or the implementation of other substantive, moreover, radical steps. In particular, parallel to the course of the campaign, the developments in the political field led to the 2020 July clashes on the Armenian-Azerbaijani border. In response to this event, Anna Hakobyan appealed to Azerbaijani women and mothers to stop hostilities and pursue peace pointing out that there is always an alternative to war.[14]

The reaction of the Azerbaijani side to the remote dialogue attempt acquired problematic manifestations. Virtually, the discourse of waging a conflict permeated the peace campaign from its start:

“On the other side of the border, they are concerned that the visit of honorable Russian ladies to the Karabagh-Azerbaijani border from the Armenian side means supporting the position of the Armenian side. I would like to highlight once again that the “Women for Peace” campaign does not aim to enter the realm of substantive regulation. It aims to exclusively protect the young lives of both Armenians and Azerbaijanis. And in order to avoid any misunderstanding on this account, I suggest that you also visit the opposite side of the contact line and send the same message from there as well.” [15]

Nonetheless, what was the message of the “Women for Peace” campaign that was supposed to unite the women of the region: Armenia, Karabakh, Azerbaijan, Russia, and even other countries? The two essential components that made up the core of the campaign were the interpretation of the phenomenon of peace and the formulations of women’s participation and role.

In the scope of the campaign, peace was interpreted as:

- At the basic level, a “natural” and understandable phenomenon, a human and ordinary situation. Nevertheless, to hold on to and talk about the fact that peace is self-evident in a state of war requires a special effort. Addressing the horrors of war that are known to mankind, Anna Hakobyan emphasizes the “less” attention given to peace in a “non-war” state.[16]

- The next layer is the ideological interpretation of peace. This is a reference to people acknowledging peace, having an idea of it in their minds. Highlighting the need for legal documents and agreements on peace, Anna Hakobyan considers the “acknowledgment of peace in people’s minds and hearts” to be overriding, and only sees the complementarity of these two as a possible path to peace. [17]

- At the third level of peace discourse, the question of goal and result is formulated: what does peace give? Peace is a state ensuring progress and development for which people need to make an effort. In the state of war and loss, everyone’s effort counts in terms of achieving peace as a daily work. Adding to the previous interpretations and summarizing the ideas about peace, Anna Hakobyan considers the actual result of peace to be critical in the discourse of the campaign, the possibility of translating what is written on paper into reality, the peace that ensures conditions for development and prosperity.[18]

Addressing the other key issue of the campaign, the interpretation of women’s role and participation, it is noted that they derive mainly from women’s family statuses (mother, wife, sister) and do not outline the whole range of public roles. Thus, in the context of the campaign, the following roles of women were circulated:

- Women as mothers in solidarity with other mothers. The circumstance of women being mothers is discussed here, regardless of nationality and other features. For a woman, in this case for a mother, the nationality of a soldier killed in the conflict doesn’t matter. Based on the claims about the influence of women on decision-makers, Anna Hakobyan called on women to unite and not allow their children to be killed, regardless of their nationality.[19]

- Women as grieving mothers. The campaign was aimed at promoting the idea that there are no more grieving mothers due to the establishment of peace. Listing the effects of wars – the obliteration of young soldiers’ lives, the orphaning of many families, and the continuous increase of mothers in black in both countries, Anna Hakobyan addresses her appeal and questions to the women themselves: who but women and mothers endure the eternal grief of the loss of their children? Who but women and mothers should raise their voices for peace? Who but women and mothers can influence decision-makers? [20]

- Women, as assistants in the spread of peace and “the one who gladly cedes the hard task of settlement to men.” With this formulation, women’s role in the process of spreading and establishing peace is limited to having an influence on the decision-makers and gladly ceding the hard task aimed at the origin of the conflict and its resolution to men, urging men to spare the lives of Armenian and Azerbaijani young men.[21]

A Peace Campaign without Criticizing the Army and Politics

While attaching importance to Anna Hakobyan’s meetings and discussions with the parents of soldiers killed in the army (those killed in the April 2016 escalation, with parents of soldiers killed in peaceful conditions), mothers and wives of soldiers killed in the Second Karabakh War, it should be noted that this campaign circumvented the constant and systemic problems of the army murders, suicides, tortures, discrimination, which are fatal even after the Second Karabakh War.

Within the scope of the “Women for Peace” campaign, the correlations between the question of peace and the problems of the army were not formulated despite Anna Hakobyan’s visits to the border military units and her attention to the army[22], or, perhaps, due to that attention. From the perspective of leading the peace campaign, Anna Hakobyan’s military uniform during her visits to the army was a sign of fondness of army. The clothing brought forth an additional semantic weight of militancy, the synthesis of which with peacebuilding efforts gave rise to questions. In addition, parallel to the importance of women’s role in calls for peace, Anna Hakobyan’s steps were aimed at women’s engagement in the military.

“…All developed countries have long tasked themselves with increasing the number of women in their defense systems as studies have shown that the armed forces where women have a greater presence are much more effective. In addition, according to international studies, the world will be more peaceful and safer if women have a more serious and profound role in defense and security issues and, even more so, in the processes of conflict resolution and peace establishment.” [23]

This approach did not take into account that advocating for the involvement of women in the military further expands the scope of militarization. Moreover, during a meeting with active women in Karabakh in May 2020, Anna Hakobyan spoke about the required involvement of women during a military attack.

“I am convinced and confident that in case of military aggression against Artsakh, not only our army but also our entire society will stand in the positions of its defense – military or civilian, male or female. Like me, many women, I am sure, are ready to take up arms to protect their motherland and children. But this is not for the sake of war, but to prove that peace has no alternative.” [24]

Anna Hakobyan’s positions on the engagement of women in the military evolved into practical steps in August 2020, when in the scope of the “Women for Peace” campaign, a group of women in Karabakh participated in a seven-day combat firearms drills for the sake of “peace.”[25] This was followed by the announcement[26] of women’s military exercises to be held jointly with the Ministry of Defense of Armenia, the purpose of which was to familiarize women with military life and military skills. In retrospect, we can claim that these were signals of the fragility of the “Women for Peace” campaign that predetermined the formation and participation of the women’s squad led by Anna Hakobyan in the Second Karabakh War.

One of the problematic aspects of the interpretation of peace within the campaign was its depoliticization.

“I am not even talking about political peace. It is the business of politicians and world leaders to negotiate that. But as long as the incentive for such negotiations is peace solely for one’s own people and not for all men and women, as long as the incentive for such negotiations is peace for our time and not peace for all time, such negotiations will not serve their purpose.”[27]

Thus, in order not to take on additional powers in the settlement of the conflict, and not to create the impression of being involved in the negotiation process, the value of peace was depoliticized and often mythologized. Any conflict in itself has a political nature, and a question arises: how is it possible to peacefully settle it, how is it possible to convey the call for peace to the political entities without politicizing the process? In her speeches during the campaign, Anna Hakobyan insisted that the policymakers themselves should resolve these issues, and women could simply take on the role of promoting the spread of peace.

In this approach, we can again notice the reproduction of the auxiliary, derivative role of women in peace which is familiar to us from the texts of female figures of the previous century. On the one hand, the depoliticization of the idea of peace can be observed as evidence of the failures or ineffectiveness of the political settlement of the conflict, on the other, however, by depoliticizing the issue, Anna Hakobyan circumvented the tangible challenges of the complex relationship between peace and war, driving the campaign even further into the symbolic field.

The Declarative Nature of the Campaign and the Trap of the Symbolic

Throughout the campaign, the texts about the role of women in the peace process were structured as appeals focusing on the need for peace. This speaks about the purely declarative (impractical) nature of the campaign which Anna Hakobyan did not conceal either.[28]

Although the launch of the campaign was a remarkable step in itself, its rhetoric was for a long time limited to appeals to women for peace from various significant platforms without offering any formal mechanism to join and contribute to the campaign. In the absence of mechanisms to join the campaign, we notice that some groups of women chose their own ways to support it. It is about having jewelry made of molded bullets perceived as a symbol of the campaign. As the first step of the campaign, Anna Hakobyan stated during the visit to the frontlines with the Russian women who joined it:

“…I believe that all the bullets in the world will melt in the face of the cosmic love of mothers. For example, they will turn into the kind of jewelry I am wearing right now. The jewelry I currently wear is made of melted bullets. It turns out that there is a craftsman in Yerevan who makes jewelry from melted bullets. I didn’t know, I found out about it recently. But as soon as I found out, I thought they would become the symbol of the “Women for Peace” campaign. And every woman who joins the campaign will have such a piece of jewelry. This means that the more women join the campaign, the more bullets will disappear from the world, lose their original meaning and become just an ornament. And this, in turn, means that so many lives will be saved. Of course, this is the language of symbolism but agree that it is not far from reality.” [29]

In fact, the bullet jeweler made them from already fired cartridges. As a result, jewelry made from fired cartridges already used for military or military training purposes, became a symbol of the campaign, raising the question of the conflicting relationship between pacifist nature and wearing ammunition as jewelry. Nevertheless, the statement had its effect. The declared symbol of the “Women for Peace” campaign was used by the jeweler to commercialize the idea of peace and promote his own initiative. Many women, from Armenia and abroad, wanting to join the campaign and not having an alternative to participating actively, resorted to buying symbolic jewelry from the jeweler.[30]

In parallel, Anna Hakobyan was working on making the campaign more institutional. During her visit to Karabakh in May 2020, at a meeting with local women active in various fields, she presented the website covering the “Women for Peace” campaign. It was part of the official website annahakobyan.am and gave a more structured and practical nature to the campaign, allowing individuals and organizations to join it online. The website presented the background, mission, values, and goals of the campaign in a more systematized way, as well as publicized the declaration of the “Women for Peace” campaign more clearly formulating and emphasizing the role of women at the core of the calls for peace. It should be noted that after the Second Karabakh War in 2020, the link to the “Women for Peace” campaign is visible on the official website annahakobyan.am, but the related section and the speeches and messages developed within its scope are unavailable.[31] This makes it evident how the war defeated the as-yet-unaccomplished initiative of women’s important involvement in the formation and establishment of the peace agenda, leaving the field to the dominant discourses of militancy and the men leading them. Thus, in fact, the activity of the campaign was interrupted.

The Escalation of the Conflict and the Freezing of the Peace Campaign

The Second Karabakh War made the fair need to criticize the apolitical and symbolic layers of the campaign evident. Perhaps, we may consider Anna Hakobyan’s letter and appeal addressed to the first ladies of different countries in the first days of the war as the last step in the campaign:

“…I assure you that with this step you will bring peace to all the peoples of this region, including the people of Azerbaijan whose innocent children, due to the actions of the tyrannical and terrorist government of that country, are being killed along with our children on the battlefield today. I want you to know that my son, Ashot, at this very moment (October 8) as I am writing to you, is on his way to the frontline in a military bus with fellow soldiers. And I want you to know that my son’s life is also at stake for peace.”[32]

While this call to the external audience emphasized the struggle for peace, in the speech addressed to the internal audience, we notice a clear change in the language and wording: the call to fight, to die for the sake of the motherland.

“On the way to Artsakh, my husband told me that our son should also go to posts as a reservist. I told my son on the way to Stepanakert. “Please be well aware, I adore you, but there is nothing nobler in this world than dying for the motherland.” I have said this for the rest of the life to come. No circumstances can change those words in me as a mother, neither today, nor a year, nor ten years from now. And I know that I am not the only one, not that I am not the only one, but I am one of hundreds and thousands as a wife and mother, and that is our victory.” [33]

When addressing participation in the war with the women’s squad, Anna Hakobyan asked if women were not ready to join the peace campaign, then why they did not join her call to participate in the war, making the problematics and the need for self-reflection on her approaches and the content of the campaign even more evident.

The war marginalized the “Women for Peace” campaign and the issue of women’s role in the peace process.

Thus, the Second Karabakh War transformed the role of women calling for peace, contributing to the peace process in one way or another, to the role of fighting women.[34] During the Second Karabakh War, Anna Hakobyan, a supporter of increasing the involvement of women in the military sector and taking up arms and fighting if necessary, was criticized by civil society, various political forces, and broad segments of the public. The core of the criticism was the creation of the “Erato” detachment which cast a shadow over the “sincerity” of the “Women for Peace” campaign. The creation of the “Erato” women’s detachment crystallized the superficial and problematic approach that Anna Hakobyan was guided by in her struggle for peace.

After the war, the social roles attributed to the wives, mothers, and sisters of the victims were enforced again, the voices of those who taught them to “correctly” experience the pain of their loss, and the moral pressures and criticisms of living an active public life intensified. Various groups serving political interests tried to use this issue to build their political careers. Criticizing the public discrimination and restrictions towards soldiers’ loved ones after the war, Anna Hakobyan framed the role of the widows and mothers of those who were killed in the war as strong women who contribute to strengthening the country and fight against injustices.

It is noteworthy that similar discourses are characteristic of post-war societies: they are unfolding in Azerbaijani public speech as well. Wives and mothers of those killed in the army and war are consecrated as long as they have no demands from the state and are at peace with their husbands who are in severe psychological and physical condition as a result of the war.

“… They are only praised when they are unquestioning, undemanding, and at peace with their trauma — otherwise, they are considered undesirable… Aside from its glorification of martyrdom at the expense of trivializing other people’s trauma, you will notice that the campaign also attempts to thrust upon widows of soldiers the responsibility of being strong, militant, and able to come to terms with their pain. [35]

By and large, the [symbolic] campaign for peace was replaced by a means of providing humanitarian and social support to war-affected families. The campaign’s activity on international platforms also became a platform for fleeting conversations about peace from the same platforms and reduced the role of women in the peace agenda completely handing over the activity to the government. “The government is doing everything for the establishment of the peace agenda.”[36]

Almost two years after the war, reviewing the freezing process of the “Women for Peace” campaign, it is important to continue to question whether peace campaigns in Armenia and women’s campaigns, in particular, can conquer the public and political arena with new and more radical content and what actions and needs there are along the way.

Author Mariam Khalatyan

Supported by Women’s Fund Armenia in the framework of the project “On the Right Track: Establishing a European-Latin American Alliance of Women’s Funds to defend human rights and the values of democracy, freedom and diversity from the attack of the rising religious conservatism and the right-wing” implementing by the collective of women’s funds in Europe and Latin America.

Supported by WECF-Germany in the framework of the project “Her Portrayal, Her Rights – Ethical Media in the Caucasus”.

References

- Yesayan, Z․ (1911). Woman for Peace. Aragats, 36-37․ New York.

- Enloe, S․ (2018)․ Feminism and Militarism (Khachatryan, G․, Ghazaryan, A․ Trans․)․ Avagyan, Sh․ (Eds․), Feminist Theory Anthology (74-95). Heinrich Böll Foundation.

- Peilerian, M․ (1914). Upward.

- Awodola, (2016, October). Peacebuilding in Africa: A Review of the African First Ladies Peace Mission. Conflict Studies Quarterly, Issue 17, 17-31.

- Liddington, J․ (1989). The Road to Greenham Common: Feminism and Anti-militarism in Britain Since 1820. Syracuse University Press.

- Masitoh, D. (2020). The Success of Women’s Participation in Resolving Conflicts in Liberia. Journal of Governance, Volume 5, Issue 1, 71-90.

- Moynagh, M., Forestell, N. (eds.). (2012). Documenting the first wave feminism. Transnational Collaborations and Crosscurrents, Volume 1. University of Toronto Press.

- Rowe, V. (2009)․ A History of Armenian Women’s Writing 1880-1922, Cambridge Scholars Press Ltd., London․

[1] 1in․am․ (2011, January 9,)․ Arzu Abdullayeva’s farewell letter in memory of Anahit Bayandur. Retrieved from: https://www.1in.am/6272.html։

[2] For this activity, they were jointly awarded the Olof Palme International Peace Prize by the Riksdag (Parliament) of Sweden.

[3] Ghazaryan G. (2020, December 25). Women on the Roadside of the War․ Retrieved from: https://ge.boell.org/en/2020/12/25/kanayk-paterazmi-campezrin

[4] Snip, I. (2020, November 3). Ignoring Women’s Voices in Nagorno-Karabakh War is an Obstacle to Peace. Retrieved from: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/ignoring-womens-voices-nagorno-karabakh-war-obstacle-peace/

[5] Mari Beilerian (Western Armenian writing: Mari Beilerian) was born in Constantinople. In her early youth, she was an active member of the Hunchakian Party, she was one of the organizers of the “Bab Ali” peaceful demonstration on September 18, 1895, because of which she was persecuted and had to go underground, taking refuge in Egypt. In 1902-1903, in Cairo, she founded and edited the Artemis family literary journal which gave women the opportunity to be involved in the public domain. It stirred interest among women readers of the time enabling the presentation of women’s lives and problems. The peculiarity of the journal was that it allowed any woman to make her voice heard regardless of public speaking skills and experience. Mari Beilerian herself (not only on the pages of Artemis) authored short stories, and journalistic and publicist texts mainly focusing on Armenian women’s rights, education, work, and charity issues. She taught in the female schools of Constantinople, Smyrna, Eudocia, and Alexandria (See Rowe, V. (2009): A History of Armenian Women’s Writing 1880-1922, Cambridge Scholars Press Ltd., London). On April 24, 1915, and in the following period, Mari Beilerian was among the Armenian intellectuals persecuted and killed in the Ottoman Empire.

[6] Bilal M ․ (2020, July 16)․ The Armenian feminist mind of the beginning of the 20th century about anti-militancy and people’s right to self-defense. [webinar]: Fem library. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3fjSDOy

[7] Ibid.

[8] 1in.am. (2011, January 9). Arzu Abdullayeva’s farewell letter in memory of Anahit Bayandur. Retrieved from https://www.1in.am/6272.html

[9] annahakobyan.am. (2018, July 25)․ Speech of RA Prime Minister’s wife Anna Hakobyan at Moscow Tretyakov Gallery. Retrieved from: bit.ly/2SlHPXW

[10] annahakobyan.am․ (2018, October 7). Anna Hakobyan visited the frontline with the Russian women who joined the “Women for Peace” campaign. Retrieved from: http://bit.ly/2Mjt2dH

[11] annahakobyan.am. (2019, April 3). The speech of RA Prime Minister’s wife, Chair of the Board of Trustees of “My Step” and “City of Smile” Charitable Foundations, Anna Hakobyan, at the US Congress ․ Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/2BjN9ox

[12] During the Fourth UN World Conference on Women (1995, Beijing), the First Lady of Nigeria, Maryam Sani Abacha, addressing the problems of women in Africa, raised the issue of gender equality related to the involvement of women in the processes of settling national, regional and global issues. In light of this, the issue of peace in Africa is highlighted, without which, according to Abacha, women in Africa will be unable to realize their potential and improve their quality of life. The voicing of issues related to women at this conference, and later the implementation of various regional events, formed the basis for the First Ladies of Nigeria, Gambia, Benin, Uganda, Lesotho, and Burundi to draft the “Declaration of Peace” in 1996, which, after being presented to the Organization of African Unity, marked the formal establishment of the initiative. The “African First Ladies Peace Mission” initiative aims to contribute to the establishment of peace, to eliminate the consequences of war which are especially severe for women and children. (Awodoloa, 2016).

The “African First Ladies Peace Mission” campaign has had a great impact over the years and is still active today. More details about the campaign are on the Facebook page of the campaign at: https://bit.ly/2N5WjYJ

[13] Peacemaker-activist Leymah Gbowee founded the “Women’s Peacebuilding Network” in Liberia in 2002. The mass movement of women for peace in 1999-2003 was a response to the second Liberian Civil War. The movement began with a small group of women who tried to win their participation in the decision-making process through ritual and other radical actions. Under the leadership of Gbowee, the movement managed to meet with the then president, Charles Taylor, to achieve the president’s resignation, as a result of which a female president was elected in Liberia, and a large number of women participated in the elections. Women’s agency increased and lasting peace was established within the country. (Masitoh, 2020).

[14] medialab.am․ (2020, July 13). Call to stop hostilities and move towards peace. Anna Hakobyan. Retrieved from: https://medialab.am/80652/

[15] annahakobyan.am․ (2018, October 7). Anna Hakobyan visited the frontline with the Russian women who joined the “Women for Peace” campaign. Retrieved from: http://bit.ly/2Mjt2dH

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] armtimes.am. (2019, April). Anna Hakobyan’s speech at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from: https://armtimes.com/hy/video/6512

[19] annahakobyan.am (2019, April 4)․ Anna Hakobyan’s speech at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3hB0fyw

[20] The speech of RA Prime Minister’s wife, Chair of the Board of Trustees of “My Step” and “City of Smile” Charitable Foundations, Anna Hakobyan, at the US Congress․ annahakobyan.am․ (2019, April 3). Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/2BjN9ox

[21] annahakobyan.am (2020, October 7). Anna Hakobyan visited the frontline with the Russian women who joined the “Women for Peace” campaign. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3hDa1QM

[22] annahakobyan.am. (2020, November 28)․ Anna Hakobyan visited the border town of Movses․ Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/2YcKsOW

[23] annahakobyan.am. (2019, December 12)․ “You are the ones who don’t spare efforts day and night to keep the borders of our country strong” Anna Hakobyan met with female cadets of the military training institutions under the Ministry of Defense. Retrieved from: http://bit.ly/2Ts9aaa

[24] annahakobyan.am. (2020, May 20)․ Anna Hakobyan met with women active in Artsakh in Stepanakert. The official website of the “Women for Peace” campaign was presented. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/37HFQDl

[25] epress.am. (2020, September)․ Anna Hakobyan and the women of Artsakh passed the combat training for peace. Retrieved from: https://epress.am/2020/09/02/1640-4.html

[26] Within the framework of the program, the participants will be trained for 45 days in barracks conditions, acquiring soldier skills. The daily life of the participants will be organized according to the format common in the Armed Forces, according to the daily schedule of the military unit: wake up at 6:30, physical exercise, breakfast, classroom and field exercises, etc. See armtimes.com. (2020, September)․ On the initiative of Anna Hakobyan and with the support of the RA Ministry of Defense, military drills for women aged 18 to 27 will be held. Retrieved from: https://www.armtimes.com/hy/article/196136

[27] annahakobyan.am․ (2019 April 4). Anna Hakobyan’s speech at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3hB0fyw

[28] annahakobyan.am․ (2020, July 13)․ Anna Hakobyan, “The aim of the “Women for Peace” campaign is to remind that the victims on the border are not statistics, but real lives, and we have no right not to be accountable for every life.” Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3ecpIwa

[29] annahakobyan.am․ (2018, October 7). Anna Hakobyan visited the frontline with the Russian women who joined the “Women for Peace” campaign. Retrieved from: http://bit.ly/2Mjt2dH

[30] We learned about this from the Facebook page of the same jeweler where there is a photo album “Women for Peace.” Here are the pictures of all the people who bought the jewelry from the master. The pictures are captioned with each one’s profession, location, and a text stating that by purchasing the jewelry, they joined the “Women for Peace” campaign. Politicians, public figures, artists, and journalists are among those people. Details at: Hayar Jewelry Artak Tadevosyan. Facebook. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/2YNHAHn

[31] Due to the unavailability of the section, links to some quotes have been replaced with materials from other media sources.

[32] a1plus.am. (2020, October 21). My people are in a forced war. Anna Hakobyan appealed to all the First Ladies. Retrieved from: https://a1plus.am/hy/article/382980

[33] annahakobyan.am. (2020, September 30)․ Anna Hakobyan met with female parliamentarians of Artsakh in Stepanakert. Retrieved from: https://infocom.am/hy/article/37568

[34] On October 26, Anna Hakobyan, following the call of her husband, RA Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, declared that she was creating a women’s squad that would go to Karabakh and participate in combat operations. After a ten-day training and examination, the squad departed to posts to perform a combat mission. Anna Hakobyan continued to remain in posts with the “Erato” women’s detachment even after the tripartite statement on the cessation of hostilities.

[35] Shahmarzadeh, N․ (2022, April 16)․ The silent victims of war․ Retrieved from: https://oc-media.org/opinions/opinion-the-silent-victims-of-war/

[36] annahakobyan.am (2022, July 7). The wife of the Prime Minister visited Nerkin Hand. Retrieved from: https://bit.ly/3OJI1tW

Funded by