What is the understanding of the region that has gone through violent conflicts and wars in different historical periods and how is Armenia understood in that region? What relations does Armenia have with its regional neighbors, and what are the preconceived notions determining the nature of regional relations? Where is Armenia in the world? The scope of our research covered these issues, inter alia, which became relevant in the public and political sphere following the Second Karabakh War.

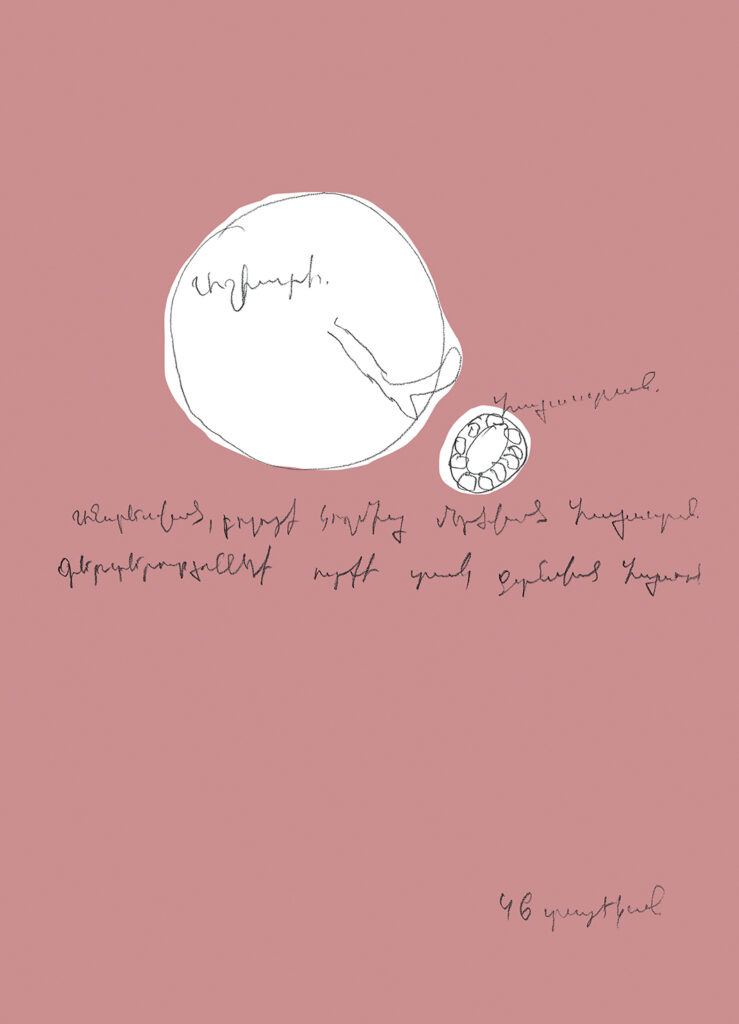

From the perspective of relating to different political entities both in the region and in the world, Armenia is interpreted by different segments of the public as being exploited, marginalized, isolated and deprived of any chance of having influence. Armenia is portrayed to the public as a small entity in a big world. In a metaphorical sense, Armenia is a “ball”, which is continuously kicked from one side and the other, deprived of its sovereignty and agency.

“Compared to the rest of the world, Armenia is very small. Connections with it [the world] are volatile, not so clear. It also has a low position in comparison with the regional countries. Whoever wants to, puts pressure on it.”

A woman aged 54-71, Artashat, Ararat Province

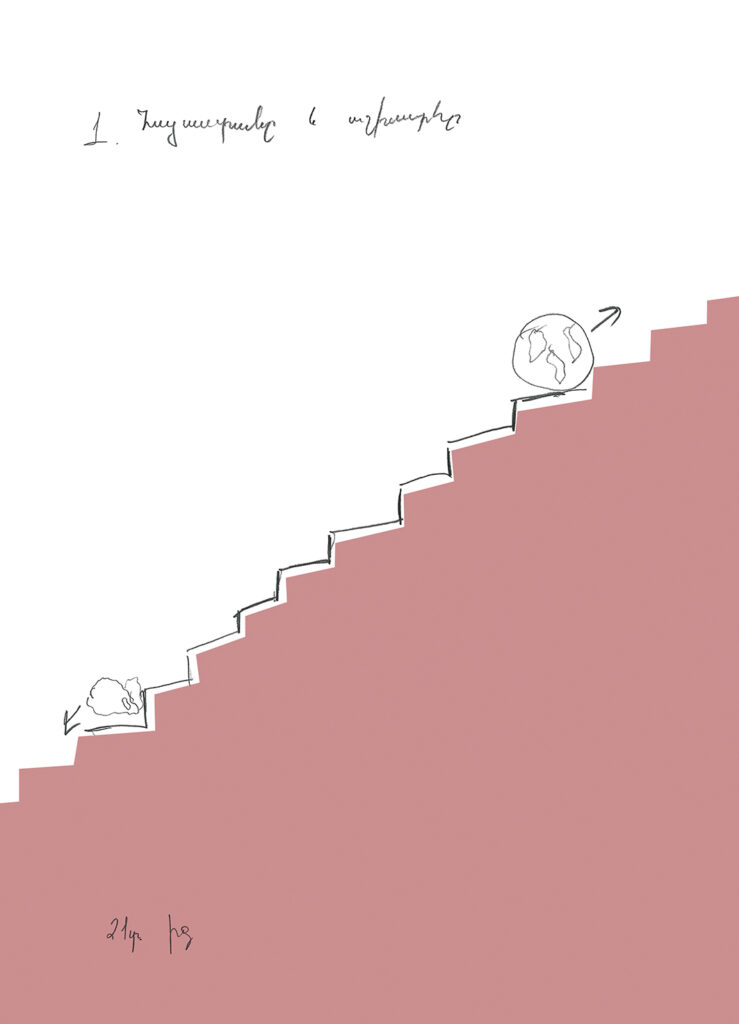

Along with the judgments about the current marginalized geopolitical situation of Armenia resides the mythical collective knowledge of the one-time “sea to sea Armenia”, Armenia as a crossroad of culture and civilization, as a country with a uniquely rich culture in the world. On the one hand, this knowledge feeds national vanity, on the other hand, it shrewdly brings up a public inferiority complex, a sense of injustice about the lost history in the background of the multiple problems of the present. The perception of Armenia as the one time cradle and crossroad of civilization, on the one hand, and the arana of wars, the bully and the victim, on the other hand, is, in fact, the manifestation of the same mythologized collective knowledge established by historical determinism.

“This is the globe, Armenia is in the center. That is how it really is. The most important roads pass through Armenia, separating Europe from Asia, the north from the south. Actually, I consider Armenia’s position as a strength in terms of development. It is very favorable. And I have always been against the idea that history teachers express at school, claiming that our position is very bad, because we are at the point of collision between superpowers. We just have not found our right positioning. Position yourself correctly, let them depend on you.”

A man aged 18-35, Charentsavan, Kotayk Province

“Mine is more of a wish that Armenia always be at the center of the world, and the world surrounded by it.”

A man aged 36-53, Yerevan

“Who knows the place of Armenia”, “the world is blind”, “the world is rising, Armenia is falling”, “as if we are outside the globe” widespread formulations among the public attest to the understanding of Armenia as lacking political agency compared to other states, constantly betrayed and helpless.In relations with other political entities, Armenia is often perceived not as a party to relations, but as a constant victim.

“Armenia and the world… The world does not have ears, it has a bright, beautiful glance, looking elsewhere. Armenia needs help.”

A woman aged 18-35, Meghradzor, Kotayk Province

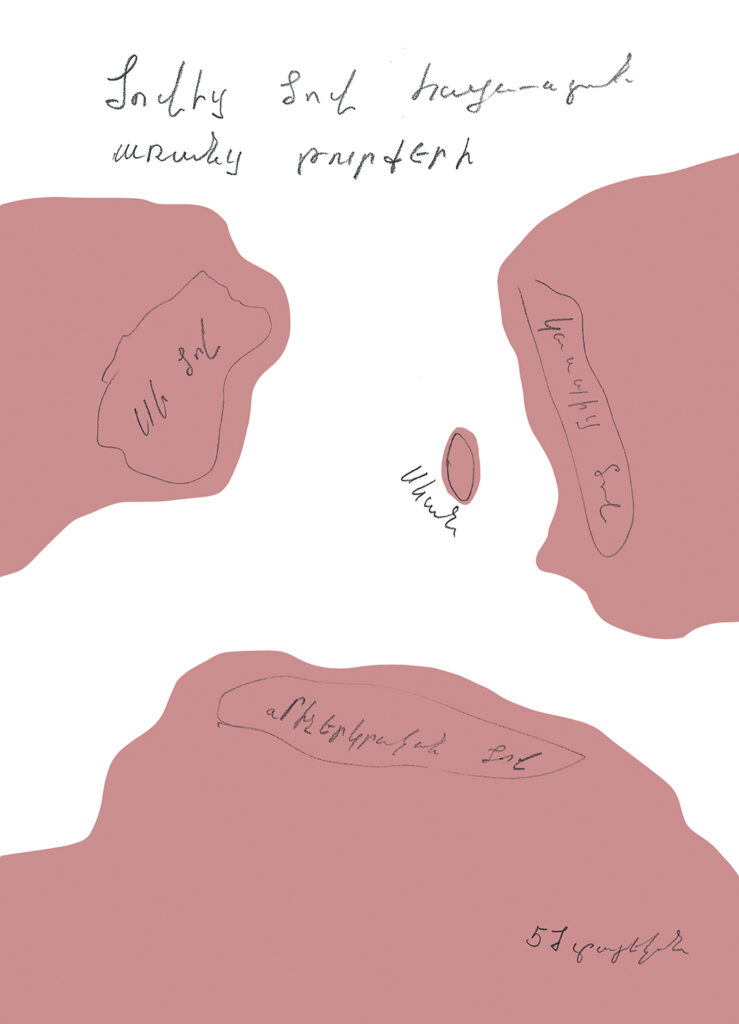

Public attempts to locate Armenia in the region reveal important implications and layers.

The mindset of being geographically located in the region, but not feeling part of it, placing Armenia outside the region, separating it from it and not seeing it as a political unit is dominant not only among the Armenian public. This understanding has historical roots and is characteristic of other regional states and societies as well, due to a number of historical and political reasons and circumstances. So how to get to study the region and find ways of interaction within it in the current situation?

As Jirair Liparitian writes in his Third Armenian Republic: The Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict, the three republics of the region never thought of themselves and did not act as part of the region. “Be it for economic development or security reasons, Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia have replaced Moscow, the capital of the Soviet Union, with Moscow, the capital of Russia, the United States and the European Union, despite impressive proposals and manifestos on major regional cooperation projects” (Liparitian, 2022։ 260). At the same time, the historian brings up an important layer – the lack of real regional thinking still does not mean that the futures of the three republics are not interconnected. They are interconnected both in terms of economy and security. However, the confrontation of these states with the conquerors dominates their collective memory, making security concerns paramount in public and political thinking (Liparitian, 2022).

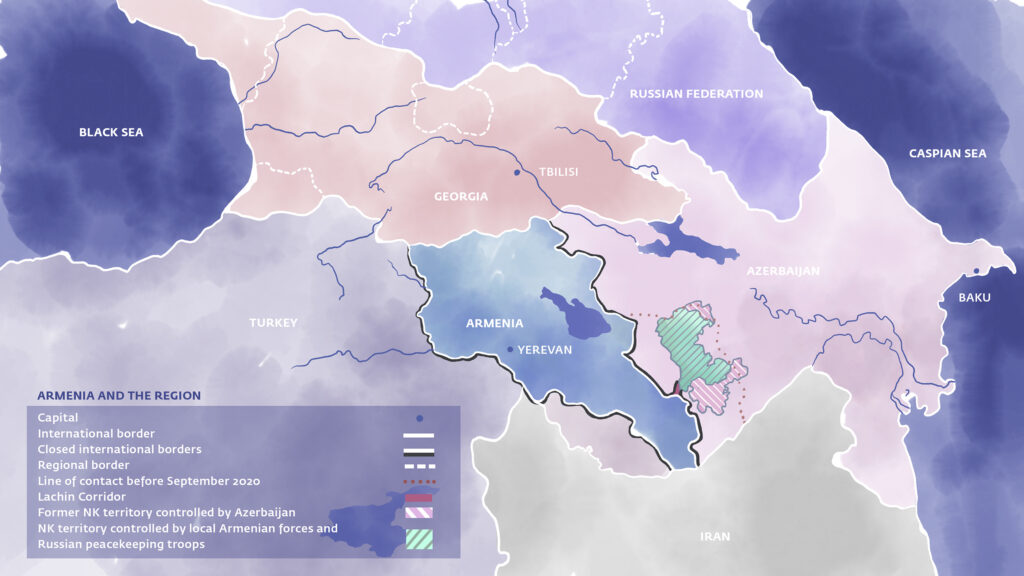

The South Caucasus, surrounded by the superpower Russia and two major regional states, Iran and Turkey, has historically been a crossroads of conflicting political interests and a significant hub of transnational infrastructures.[1] This circumstance makes it an area of interests and influence of the superpowers, and also arouses the interest of the great powers that do not directly border it.[2]

Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan have come a long way since independence, and have done so with differing geopolitical preferences, wars against each other, disagreements, competitive relations.

The Soviet Union united these three republics under the ideology of socialism and “brotherhood of peoples” in a certain framework of coexistence, which masked the controversial and problematic pages of historical relations between political entities (Kharatyan, Hakobyan, 2019). The Karabakh conflict and wars made the experience of years of coexistence of peoples sink into oblivion. In the background of complicated relations with neighbors in the South Caucasus region, closed borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan, maintaining normal relations with Iran was one of the fundamental principles of Armenia’s foreign policy during the years of independence․ This policy was also justified by Iran’s neutral policy towards the Karabakh conflict, in contrast to Turkey, who is Azerbaijan’s partner in diplomatic and political terms (Liparitian, 2022).

From the perspective of political science, the economic and political development of the state is connected with the region in which the given state is geographically located.[3] In this context, mutual interest and connection become especially important, making the issue of independence and sovereignty even more relevant. In this sense, we can observe that after the Second Karabakh War, the “informed” choice of the extent of Armenia’s sovereignty and independence, external influences and orientations have become dominant in both the public and political discourse, framing the ability to ensure security within the context of normalization of relations with neighboring countries.

The Second Karabakh War, the change of the status quo and power relations in the region led to rethinking of the region and Armenia’s place in it. Although the Second Karabakh War is an opportunity to rethink relations and roles in the region, the complex process of rethinking takes place in a historically formed and loaded context, so it will require years of self-reflection. Despite the attempts of political and public rethinking of Armenia’s relations in the region and with the region (the relations between Armenia and neighboring states in the region are often compared with the ability to communicate with neighbors in everyday life), relations with neighboring countries are largely perceived as a given and not subject to transformations of the historical context and processes. Public debate on the tough relations are expressed by “it comes from centuries ago”, “it has always been like that”, “Turks will be Turks”, “we have seen Genocide”, “they committed Genocide” and other similar expressions.

However, the chain of interpretation of this tough and unchanging nature of relations is interrupted, for example, in the process of locating the relations with Iran in the historical context, determining the change of relations in time and space, where the key point of departure is again the Second Karabakh War.

“Peace is a very difficult endeavor for Armenia… Look, today we say Iran will [help]. Do you think Iran did not massacre us?” Now we are in such a state that we are kissing the hand of the slaughterer again. The slaughterer… Because it is better… Yes, they have slaughtered us, but now it is the good. We must be strong, have an older brother.“

A man aged 18-35, Nalbandyan, Armavir Province

Thus, we can observe that public perceptions of the nature of relations of Armenia with the region and neighboring states, and their transformations are largely conditioned by the historical context and politics of memory, the fresh trace and trauma of the Second Karabakh War, elderly people’s experiences of the Soviet past, daily media manipulations and speculations by forces with different political interests.

The ideologeme of “sea to sea Armenia” is popular both among youth and the elderly. However, it is noteworthy that for the public it has no potential to become reality. Rather, it has become a cultural mantra we are used to repeating in schools, in history lessons, at social gatherings in the form of toasts, or during those tedious debates with Turkish and Azerbaijani politicians.

“I painted Armenia from sea to sea and I think that the time will come when our generations will be proud to get back our homeland again, and our borders will stretch from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea.”

A man aged 18-35, Gyumri, Shirak Province

Public understandings of Armenia’s role and relations in the region or in the world are not only linked to the past, but also to the future. The relations with other states and the boundaries of one’s own political agency are conditioned by the uncertainty of the future and pessimistic scenarios at the geopolitical level, particularly emphasizing the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the instabilities it has caused.

“It is a struggle between states. It is a fight of economies… whose money will win. Maybe we will wait and see how the situation there [Russia, Ukraine] will settle down, who will win, and then maybe our situation will be a little clearer. Nothing [is clear] at the moment. Because Russia is at war, Europe and America are against Russia.”

A woman aged 36-53, Malishka, Vayots Dzor Province

It is also worth noting that in the state of defeat in war, heightened tension and hostility, people sometimes deliberately did not picture Azerbaijan in the region, as an act of protest, verbally stating that they were doing it on purpose. These isolated acts of not depicting Azerbaijan on paper, of “removing” Azerbaijan from the visual field of the region, materialize the public anger, fears and anxieties that arose after the war.

Along with having political and economic relations with neighboring states, the public also emphasizes the layer of human relations. The idea of mutual benefit prevails in the relations with Turkey and Azerbaijan, and in this sense the economic relations seem to be subject to normalization. However, the normalization of the relations between the peoples, which is formulated as friendship, is much more firmly rejected.

“It is all about interests. If the interests coincide, you are friends, and if not, you are not. If there are many interests, we are more friends. Because we are all rational people and we can’t afford not being ones. We should get out of our comfort zone.”

A man aged 18-35, Yerevan

“You are a neighbor. How long can you survive in an environment of hostility?” It’s a toxic environment. Either you will drown if you are weak, or they will devour you. So, you must understand that you are weak and, whether you like it or not, find a common language in some way, because that is what the rules of the game imply. You cannot isolate yourself all the time. You cannot move forward by isolating yourself.”

A woman aged 36-53, Ijevan, Tavush Province

“Well, now, after this war, I cannot imagine someone listening and saying, yes, let us love each other.”

A woman aged 18-35, Vanadzor, Lori Province

Even though the Second Karabakh War has further aggravated relations with Azerbaijan and Turkey, it has also given a new momentum to the public positions and discussions of relations with Georgia.

Due to its geographical location, Georgia has always been a mediator between Armenia and Azerbaijan and has not concealed its western-oriented foreign policy.[4] Armenia’s relations with Georgia, which views the Soviet past as colonial and the present as an inseparable part of the “European family”, although not openly, are still in the realm of cultural and political competition inherited from the Soviet past. The generalized evaluation is that Armenian-Georgian relations have always been defined by certain “reservations”. We can observe that media representations and interpretations of Georgia’s positions or actions during the Second Karabakh War significantly influenced the understanding of different segments of the public, making the “unhealthy” nature of Armenian-Georgian relations even more apparent (Liparitian, 2022).

Currently, the public perceptions and formulations of the relations with Georgia are framed by the moral narrative of the support it failed to show during the Second Karabakh War. At the same time, from the perspective of the war victim and the defeated party, the provision of support is formulated as self-evident, mostly without addressing the nature of Armenia-Georgia relations in the years before the war, the factors that contributed to them.

“What kind of relationship can we have with Georgia? They closed the road during the war, not allowing Russian weapons, ammunition, even ambulances to reach Armenia? Or now, they closed the road again, and all our apricots got spoiled.”

A woman aged 54-71, Artashat, Ararat Province

Armenia’s role in the region

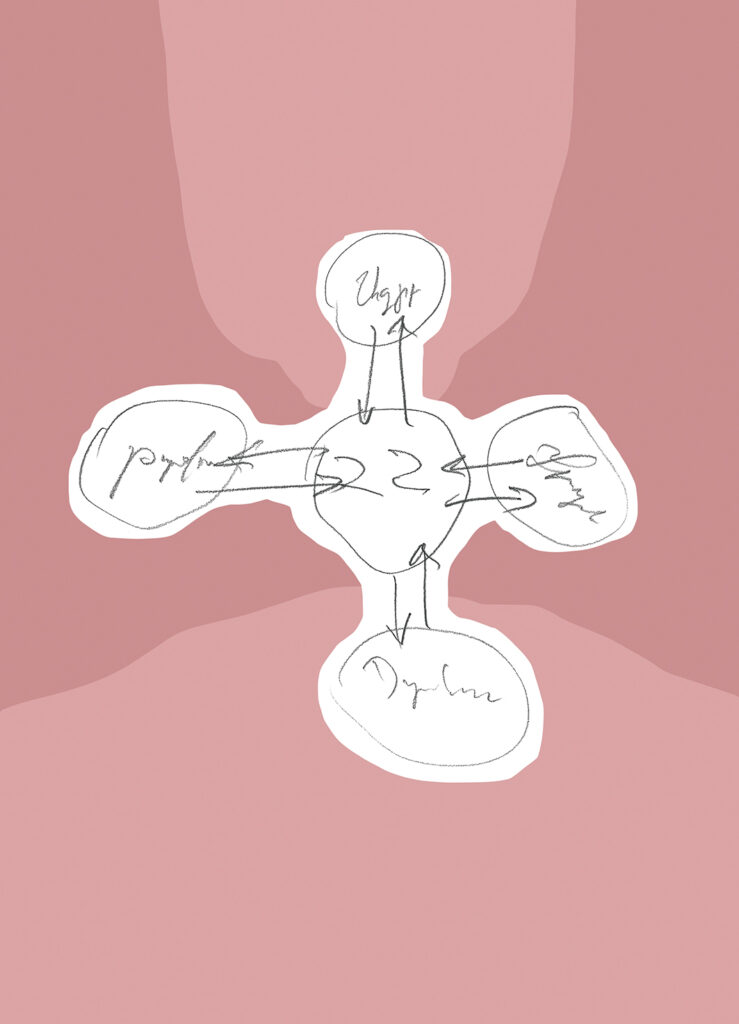

When referring to the countries of the region, particularly the South Caucasus, it should be emphasized that despite the differences in their foreign and security, domestic and socio-economic policies, they are interwoven with complex ties. Because the South Caucasus is a region of small states, the latter are sensitive to and greatly affected by world events, the policies of influential and large states, and are easily subjected to shocks (Liparitian, 2022). Although that circumstance should serve as an incentive for perceiving regional cooperation as vital, we can observe that we are dealing with the absence of regional thinking or fragility of such thinking. In fact, the region can be characterized by bilateral relations between individual states (which can also be hierarchical), rather than cooperative and broad-ranging regional relations.

Although regional analyses and assessments are reserved to political scientists, local and international experts, who have a hegemonic position in the Armenian media especially after the Second Karabakh War, we, as sociologists, find it important to reveal public understandings of the region, in contrast to the understanding among political (and sometimes expert) circles that the public does not have sufficient capacity to analyze regional events.

Our research shows that in their judgments about the region, different segments of the public rely on the analysis of the categories of interest and influences, particularly the role of Russia in the region and the extent of Armenia’s political agency. Karabakh is understood as a zone of Russian interest and influence, and Russia is assigned the role of both the instigator of the war and the “inevitable” strategic ally, with claims that the deterioration of the relations with Russia could be devastating for Armenia. It does not take much effort to note that this is not only a public but also a dominant political mentality and discourse in Armenia, which demonstrates the direct connection between the public and the political.

From this point of view, the entire South Caucasus is depicted in public perceptions as an area of Russian control, where Turkey also plays a major role. Thus, Armenia is in a paternalistic and subordinate relationship with Russia, and Azerbaijan and Georgia are in a similar relationship with Turkey. However, Iran is outside of these subordinate relations.

“The neighboring country is Turkey, with which we have no relations. Karabakh is a neighbor, we have nothing, one day [relations with] Georgia are good, another day they are bad. Iran remains the only superpower, and God knows what will come into their mind.”

A woman aged 36-53, Armavir, Armavir Province

According to different segments of the public, perceived as subordinate and lacking political agency in the region, Armenia is not involved in the decision-making process in general, neither is it involved in making decisions concerning its own fate, and is in a subordinate position in relations with other regional states.

“It’s okay with Iran, and we can say it is okay with Georgia. Azerbaijan is our main problem. My evaluation is that Russia is good. If not for their defenders, what would be the situation of Artsakh, or Armenia? But in my opinion, this is the matter of Russia. Our leadership acts as Russia tells them.”

A woman aged 54-71, Vardenis, Gegharkunik Province

“Who in the region takes Armenia’s opinion into account? They dictate to [Armenia].”

A woman aged 36-53, Armavir, Armavir Province

Taking into account the circumstance of dependence, the changeable, unstable, and situational relations between Armenia and Georgia are based on different foreign policy courses.

“Relations with Georgia are turbid, because the two countries have very different views. Georgia looks to the NATO, and Armenia to the CSTO, the CIS. That is why they always get into conflicts, and it’s not like they control their relations. They are controlled by dictating forces, to put it bluntly.

A man aged 18-35, Charentsavan, Kotayk Province

Based on our research, we can claim that the understanding of Armenia and Armenians as “victims”, without allies and surviving in a hostile environment is prevalent among the general public. At the core is the essentialist thinking and the thinking dominated by historical determinism, under which Armenia is understood as a state constantly under pressure from “predatory neighbors”. People explain the continuous state of being “oppressed” or a “victim” in regional relations by the geographical position of Armenia, the defeat in the Second Karabakh War and the following border tensions, as well as the fear of finding themselves in a potential blockade as a result of territorial losses.

It is also due to its geographical location that Armenia is perceived as an arena of wars and a toy in the hands of superpowers, a weak, small state. The perception of the role of Armenia located at the “crossroads of conflicts and wars” after the Second Karabakh War is framed by the political narrative of “the one who gives a corridor”. In this situation perceived as desperate, there is also widespread public discourse on the need to overcome the situation of the oppressed, the confined, which is mostly connected with the need to improve the socio-economic situation of the country, to diversify the paths of development.

“We have remained a crossroad, but we are not being developed, taking into account that there may be incessant changes in our region. We are at the crossroads in the region. We all know that we are at the crossroads of the Caucasus. All the roads pass by here, but they are still afraid to see development here, thinking that something might happen in the future, and the whole investment will be in vain.”

A man aged 36-53, Tumanyan, Lori Province

Despite the fickle attempts at self-reflection, we can observe that in terms of regional relations, the fossilized public mentality of victimizing Armenia and Armenians prevails. The dominant mentality of victimization significantly limits the possibility of locating Armenia as a responsible party in relations with other political entities and not as a permanent victim, continuously reproducing the perception of dependence on external forces and its own impotence.

The perception of the hopeless dependence on external actors crystallizes in public analyses of relations with Russia. We can observe that the older segment of the public calls relations with Russia fake alliance, unequal, dependent and undesirable, but sees their deterioration as fraught with impending security challenges. In this way, Russia’s policy of exertion of power and subjugation is reproduced and legitimized at the public level as well. It is obvious that for years the policies of particularly the second and third presidents, who justified the dominance of Russia with the security of Karabakh and Armenia, have found their place in public thinking. Criticism of Russia by young people is much more straightforward, and the issue of getting out of Russian influence is deemed as urgent, as an opportunity for Armenia’s sovereignty and independence. There is argument in favor of normalization of relations with Turkey (with all the ensuing consequences) as a counterbalance to Russia.

“Russia acts based on its interests. Not because we or the people of Karabakh are the apple of their eyes. They needed to deploy their peacekeeping forces in Karabakh. So, they started the war, there were so many innocent victims. But our only hope is Russia, our enemy. If we try to reach out to another state now, we will end up in a worse situation than Ukraine.”

A woman aged 54-71, Vardenis, Geharkunik Province

“The most dangerous relations for me are the relations with Russia. For centuries, as much as they have been by our side, they have been there to destroy us, to sell us out. The biggest matter of concern are the Russians. In this case, it is better to be with the Turks than with the Russians.”

A woman aged 18-35, Yerevan

In public discourse, apart from the level of geopolitical influences, the issue of the normalization of relations with neighboring countries in the region is also made sense of in the layer of domestic politics in Armenia. Domestic political cohesion[i] and acting for the sake of state interest is defined as one of the prerequisites for the normalization of relations with neighboring states in the region. After the Second Karabakh War, the domestic political situation, divided around the axis of the search for “internal traitors” and “those who sold the lands”, has led to deep-seated public fatigue. In this context, the public relates the ability to find a common language with the regional neighbors to the possibility of achieving internal political reconciliation. If we overcome this situation, it will be possible to reflect on relations with neighboring states in the region and their normalization.

Contrary to this perspective, there is the idea of a “desirable” region, where Armenia is surrounded by Christian states. By the way, the question of religious affiliation sometimes becomes a starting point for formulating the nature of regional relations, according to which the emergence of distrust between Christian and Muslim societies is more likely.

“We are a state surrounded by Muslim states. We have to get stronger from within.”

A man aged 36-53, Tumanyan, Lori Province

In discussions about regional relations, the context of the Soviet past often comes up, especially when recalling the coexistence with Azerbaijan. Nevertheless, in the recollections inherited from the Soviet years and framed by the position of a once-victorious party, the Soviet period willingly becomes a reference point, a historical period of Armenia’s dominance over Azerbaijan, a coexistence that was based on our cultural supremacy. After the Second Karabakh War, public perceptions regarding peaceful coexistence with Azerbaijan are deeply entrenched, but alongside the radical rejecting views, there are also voices criticizing such positions, attempts to sympathize with the Azerbaijani society, to parallel the tragic consequences of the war for both societies.

There are parents of victims there [in Azerbaijan], right? Naturally, that war could not be in their interest either.”

A woman aged 36-53, Armavir, Armavir Province

“The other time the people [in Azerbaijan] said: Do I want my child to go to fight? No, I don’t. Go blame the leadership, not us. Now, in the case of Armenians, Georgians, and Azerbaijanis, the leadership does that [incites], the people are not to blame.”

A woman aged 54-71, Yerazgavors, Shirak Province

Public perceptions of the normalization of Armenian-Turkish relations

From the perspective of relations with neighboring countries in the region, Armenian-Turkish relations and their public perceptions deserve special attention in the context of historical development and the new round of the negotiation process that started after the Second Karabakh War.

Although Turkey was one of the first states to recognize Armenia’s independence in 1991, diplomatic relations have not been established between the two countries.[ii] One of Turkey’s preconditions for establishing diplomatic relations with Armenia was the termination of the process of international recognition of the Armenian Genocide and the recognition of the Armenian-Turkish border as stipulated in the 1921 Treaty of Kars.[5]

The politics of memory can even obliterate the history of the recent past. In 2008, at the initiative of the third president of the Republic of Armenia, Serzh Sargsyan, a new phase of the normalization of Armenian-Turkish relations (better known as “football diplomacy”) began. As a result, the Foreign Ministers of Armenia and Turkey signed the Protocol on the Establishment of Diplomatic Relations between the Republic of Turkey and the Republic of Armenia and the Protocol on Development of Relations between the Republic of Turkey and the Republic of Armenia on October 10, 2009 in Zurich.[6]

The normalization process that started in 2008 was not a success due to various internal and external reasons, which are perhaps the subject of analysis by political scientists and historians. It should be noted that in that period the question of abandoning the precondition of recognizing the Genocide had once again become relevant in the public and political discourse. The discourses of treason and “Turkification” fueled by the Hay Dat-based politics were also dominant. In 2014, Serzh Sargsyan spoke at the session of the UN General Assembly, during which, in fact, he declared the failure of the normalization process of Armenian-Turkish relations, declaring that Turkey’s precondition is “to hand over Nagorno-Karabakh, free Artsakh, to Azerbaijan”, to which people’s (what people?) response is simple – “go to hell with your ratification”.[7] On March 1, 2018, Serzh Sargsyan’s decree put an end to the process of signing the Armenian-Turkish protocols.[8]

Turkey’s support to Azerbaijan during the Second Karabakh War, and information about the involvement of Turkish troops and military command led to a new wave of hatred and anger among the public.

The politics of identifying Azerbaijan with Turkey, the Azerbaijani with the Turk, gained further momentum in the aftermath of the war, reinforcing the public sentiment of being isolated and not having allies in the region. Despite the trauma of the Genocide and Turkey’s failure to recognize it, the Karabakh conflict remains the main factor dividing Turkey and Armenia and keeping the borders closed.

“The Turk cannot be distinguished from the Azerbaijani. We see the same in the same way, under the same flag, the same nature.”

A woman aged 18-35, Meghradzor, Kotayk Province

After years’ pause, the political process of the normalization of Armenian-Turkish relations entered a new course after the Second Karabakh War, particularly following the snap parliamentary elections held in June 2021. Ruben Rubinyan, who was elected Deputy President of the National Assembly of the 8th convocation of the Republic of Armenia from the Civil Contract Party, assumed the function of the Special Representative of the Republic of Armenia in the Armenian-Turkish dialogue process.[9] The current stage of the normalization process raised a wave of public and political debate and criticism. On February 6, 2023, the highway connecting Armenia to Turkey was opened for the first time after a long break to transport humanitarian aid after the devastating earthquake in the southeast of Turkey, on the border with Syria. Through the Margara bridge, Armenia sent humanitarian aid to the disaster-stricken city of Adiyaman, where the Armenian rescue team was working. It remains to be seen whether this political, diplomatic and humanitarian act can have a tangible benefit in the process of normalization of Armenian-Turkish relations, particularly in the matter of opening the borders.

Our research reveals vigilance and anxieties among the public with regard to the normalization of Armenian-Turkish relations, framed by the fear of “occupation” of the economic, political and cultural spheres, which is sometimes fueled by everyday conspiracy theories. At the same time, the historical past, the non-recognition of the Genocide by Turkey, the ideologized public mantra “Turks will be Turks” limit the ability of the society to situate the Armenian-Turkish relations in the historical and political present. The public attitude towards the Turks as a collective brings to light the problem of the dominance of essentialist mindsets and lasting enmity: “they will never be normalized”, “it is not realistic, it will not happen”, “how to normalize relations with Turkey if it is our enemy”.

Nevertheless, the attempt of the public to separate the present from the past is also widespread. Pointing out the importance of the past, the imperative to reduce its influence on the development and progress of current relations is interpreted as key.

“Borders should be opened so that there is free entry and exit, and trade between Armenia and Turkey. You say that you will not forgive the Genocide, right? You say, you demand, you know, but you shouldn’t connect it with this thing. We need to develop, this generation should develop. We are under siege. We say that we have so many victims, but they also have victims, they have more victims. We should not be comparing.”

A woman aged 54-71, Kapan, Syunik Province

At the same time, the existence of the Armenian community in Turkey, the coexistence of the two peoples within Turkey, although rare, is a tangible issue of discussion for some segments of the public, contributing to the visualization of the possibility of the normalization of Armenian-Turkish relations.

“During the war, we asked the people living there if there was any tension, and they would say that there was tension among the leaders, not among the common people. They said they did not feel any difference at all.”

A woman aged 36-53, Armavir, Armavir Province

The reluctance to normalize relations subsides when the issue of normalization is framed by improving the economic situation of the people and the state, revitalizing economic ties. It is often acceptable and even important for the public to normalize relations with an economically powerful country in the region and in the world.

“We will forget about Lars [as a result of unblocking transport links]… I will borrow money, work hard, plant 5-10 hectares of potatoes. In the fall, I will get 80-100 tons, bring them home, pack them, put them on a truck, drive to Persia, enter Turkey through Nakhichevan, sell them, and come back.”

A man aged 36-53, Lchashen, Gegharkunik Province

In this context, the issue of diplomatic capacity of the authorities becomes even more prominent for the public. In this regard, the inexperience and young age of Armenian representatives in the Armenian-Turkish dialogue process, in contrast to experienced Turkish diplomats, are the subject of public indignation.

Although the economic aspect of the normalization of Armenian-Turkish relations is more realistic for the public, it reveals another layer of national fears and concerns. The destruction of Armenia’s fragile economy as a result of the opening of the border is seen as a possible scenario. At the same time, reconciliation or neighborly coexistence does not derive from the normalization of economic relations. The mentality of being cautious with the Turks is dominant.

Taking into account the full range of relations with neighboring countries in the region, public discourse is built around a dominant view of realism that, regardless of friendly, allied or not so cooperative relations, each country is driven by its own interest and by the benefit it derives from those relations. Taking into account this circumstance, some segments of the public consider the diversification of Armenia’s foreign policy as fundamental. Especially young people, who think that closed regional borders kill any prospect of development, value the establishment of diplomatic relations between Armenia and regional countries, including Azerbaijan and Turkey. Of course, public sentiments of rejecting relations of any nature with Azerbaijan and Turkey are also widespread.

“It is necessary to establish diplomatic relations with both Turkey and Azerbaijan, both to avoid war and to live in peace.”

A man aged 18-35, Charentsavan, Kotayk Province

Depending on people’s experience and age, there is also a clear position that building relations with neighbors in the region is inevitable, and its rejection is illogical. Projecting the historical past on the present limits the possibilities of developing and searching for ways to regulate regional relations.

“Germany is not our strategic partner. We do not have a geographic border with America. Whether you like it or not, you have to get along with your neighbors. They have turned out to be our neighbors. We need diplomats.”

A woman aged 36-53, Ijevan, Tavush Province

Issues of unblocking and reopening transport links in the region

The issues of unblocking and reopening transport links with regional neighbors in the future are framed by the public within the categories of benefit and harm. While the ideas of enmity, victimhood and fatalism dominate the level of general judgments about Turkey and Azerbaijan, the prospect of reopening the borders and improving the socio-economic situation of the people makes the possibility of the neighborhood real and tangible, practically positive. Although building economic relations with neighbors is generally acceptable to the public, it does not necessarily imply an imminent normalization of historically loaded Armenian-Turkish and Armenian-Azerbaijani relations.

“Friendship will definitely not happen, because the generation that has seen the current political situation will definitely be against it. It is as simple as that. But the state is currently trying to lead Armenia to a state where there will be an intermediate solution. In other words, if the state tries to open a road or have diplomatic relations, it will definitely be viewed negatively by the people, it will be considered an attempt at establishing friendly relations.”

A man aged 18-35, Shinuhayr, Syunik Province

Thus, the question of unblocking transport links and opening borders has a more pragmatic formulation in the public discourse. It is seen as a way to prevent impending war[s], to avoid them. Due to lifting of the economic blockade, according to some, Armenia will return its former position as a connecting link in the region, leading to the improvement of the security situation. On the one hand, the reopening of borders in the region at the cost of minor concessions is formulated as a condition for having stability in Armenia, on the other hand, concessions in the context of various historical and political events are seen as the main reason for the current wretched state of Armenia.

“Although even one centimeter of land is crucial, they want to do delimitation [of borders]. We clearly realize that as a result we will lose something, but at least we will gain stability, on the basis of which we can achieve something.”

A woman aged 18-35, Megradzor, Kotayk Province

The issues of unblocking transport links and establishing relations between societies take on different nuances depending on the region. The closer the communities are to the capital, the “safe center”, the more unacceptable those relations with neighboring countries are, and the further away or closer to the border a given community is, the more important the normalization of relations becomes. This certainly does not mean that people living in border communities do not have concerns and anxieties about the changes and uncertainties arising from the unblocking of transport links. However, the past experience of coexistence of people in the border communities with the neighboring peoples, the intertwined life stories bring the communities closer, and the restoration of former relations becomes more tangible. Moreover, residents of border communities formulate the negative consequences of closed borders from the depth of their daily living conditions and socio-economic inequality and injustice. The public positions supporting the unblocking of transport links are particularly justified by the increase in trade turnover, which can improve the socio-economic situation of Armenia and contribute to the region indeed becoming a political entity.

“Once transport links are opened, everything will be okay. Even the commercial movement, the movement by transport, whether you like it or not, will connect the people together. To ensure that nothing happens when you drive through the road, they do not confiscate [the car] in Armenia, willy-nilly, one state must be friendly with the other, even if covertly, as we say, and everything will be okay. As long as transport links are opened, it will be okay.”

A woman aged 36-53, Ijevan, Tavush Province

“There must be roads, because if we do not patch things up, if we do not come to an agreement, this enmity will go on endlessly. Our children will be killed, and our captives will be killed there.”

A woman aged 54-71, Vardenis, Gegharkunik Province

At the same time, there is a mentality among the public nurtured by Armenian and Karabakh political and military clans and consolidated by other means, according to which Armenia is not under siege, and open borders with Georgia and Iran are sufficient for the socio-economic and political development of the country. For years, the political and military elites in Armenia and Karabakh contrasted the reopening of the borders with Turkey and Azerbaijan with fear of the Turks. Russia’s role as the only possible defender of Armenia was also legitimized by the fear of the Turks. At the same time, the reopening of the borders is framed by this segment of society as Azerbaijan’s “desire” or coercion, in a broad sense, use of force against the defeated party.

“We are not under blockade. We have a border with Iran. We have a border with Georgia. We can use that. It is safer and does not lead to collapse. For that, there should be closed roads with Turkey and Azerbaijan, and open roads with Georgia, Iran. We should work further in that direction, because if we have nothing to offer, we will be moving towards collapse.”

A man aged 18-35, Gyumri, Shirak Province

Another layer of public concern about opening borders is the issue of social justice. People are worried that the unblocking of transport links will not improve the socio-economic situation of the common people, the working class, but will lead to the enrichment of oligarchs and businessmen, and will create ample opportunities for them to accumulate large capital.

All these public concerns are the result of the trauma of the Second Karabakh War, the risk of imminent wars and escalations, the policies of Azerbaijan using force and threats. Major political processes take place alongside public anxieties and fears, generally in the background of weak and fragile pillars of trust.

“As long as there is no so-called peace on our borders, that is, there is still fear among people that every minute [war] will start again… People should have that inner peace. But every now and then there are shootings or something, and the fear [of war] starts raging in people again… If there is no peace now, how can open borders ensure it? We are giving the opportunity to our enemy to invade our borders with less effort.”

A woman aged 36-53, Ijevan, Tavush Province

Trust is generally vulnerable both at the domestic level and in terms of relations with regional neighbors. The Second Karabakh War renewed distrust towards Azerbaijan and Turkey in the region and exacerbated security issues. However, in parallel, the issue of normalization of relations in the region as a prerequisite for economic development has also become prominent.

“It is a complicated issue. We want a security guarantee. I understand that everyone is concerned about the opening of the railway. It is not like it does not bother me. Everyone wants that security guarantee, but we also have to find something positive in it. More active economic links… If that railway operates, there will be jobs, exchange of goods, etc. There can be something positive in this if we are able to properly address the security issue.”

A woman aged 36-53, Ijevan, Tavush Province

Author: Mariam Khalatyan

Editor: Arpy Manusyan

References

1․ Liparitian, J․ (2022). Third Armenian Republic, Nagorno Karabakh Conflict։ Materials for History․ Yerevan, Antares.

2․ Kharatyan, L․, Hakobyan, A․ (Ed․)․ (2019). Fragments of Armenia’s Soviet Past. Tracing the Armenian-Azerbaijani Coexistence. Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography, National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia.

[1] Hovhannisyan, D․ (2017, December 20). Armenian-Georgian Relations. Actuality of Sustainable Development. Retrieved from https://ge.boell.org/en/2017/12/20/hay-vratsakan-haraberowtyownner-kayown-zargatsman-ardiakanowtyowne

[2] Ibid.

[3]Boon TV. Boon Talk: Foreign Policy | Anna Gevorgyan | Anna Ohanyan. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=icWoLTFEbVY

[4] Boon TV. Boon Talk: Foreign Policy | Anna Gevorgyan | Anna Ohanyan. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=icWoLTFEbVY

[5] Hakobyan, T․ (2017, July 10)․ Armenia-Turkey: Hundred Years of Diplomatic Relations․ civilnet.am.Retrieved from https://cutt.ly/n85QOrt

[6] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Armenia․ Bilateral Relations․Turkey․ mfa.am․ Retrieved from https://www.mfa.am/hy/bilateral-relations/tr.

[7] Aslanyan, K․ (2014, September 24)․Yerevan discusses the issue of withdrawing the Armenian-Turkish protocols from the Parliament․ azatutyun.am. Retrieved from https://www.azatutyun.am/a/26604643.html.

[8] Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Armenia․ Bilateral Relations․Turkey․ mfa.am․ Retrieved from https://www.mfa.am/hy/bilateral-relations/tr.

[9] azatutyun.am․ (2021, December). Ruben Rubinyan will be the Special Representative of Armenia in the Armenia-Turkey dialogue process. Retrived from https://www.azatutyun.am/a/31615529.html.

[i] A detailed discussion of the issue of domestic political cohesion is included in other, not yet published, sections of the analysis.

[ii] Despite the absence of diplomatic relations between Armenia and Turkey and the land borders being closed for years, since the 1980s there were regular Yerevan-Istanbul-Yerevan flights operated by the Armenian Airlines. In September 1992, 58 thousand tons of grain were brought from Turkey to Armenia through the land border. In parallel, in 1992-1993, Armenian and Turkish diplomats worked on a protocol regulating Armenian-Turkish relations, but the protocol remained incomplete after Armenian forces invaded Kelbajar in 1993. In response, Turkey closed both borders with Armenia, and flights were also canceled. See Hovhannisyan, H․ (2022, February 4)․ The history of Turkey-Armenia flights: When did the first flight take place? civilnet.am. Retrieved from https://cutt.ly/X85Qfpf; Hakobyan, T․ (2017, July 10). Armenia-Turkey: 100 years of Diplomatic Relations civilnet. am. Retrieved from https://cutt.ly/n85QOrt: